When a child gets pneumonia or a woman develops a urinary tract infection, the expectation is simple: a pill or an injection will fix it. But in 2025, that’s no longer guaranteed. Across the globe, antibiotic shortages are turning common infections into life-threatening emergencies. Hospitals are rationing drugs. Clinicians are forced to use toxic last-resort options. And in low-income regions, patients are sent home with no treatment at all.

Why Antibiotics Are More Likely to Run Out

Antibiotics aren’t just any medicine. They’re the backbone of modern healthcare. Every surgery, every chemotherapy treatment, every premature birth relies on them to prevent infections. Yet, they’re 42% more likely to face shortages than other drug classes, according to a 2024 study in Clinical Infectious Diseases. Why? The answer isn’t one problem-it’s a broken system. Most antibiotics are cheap generics. Manufacturers make so little profit on them that they stop producing them. A single vial of penicillin G benzathine, used for decades to treat strep throat and syphilis, costs less than $2. But the cost to produce it safely? Over $10. When you add in rising regulatory requirements, factory inspections, and quality controls, the math doesn’t work. So companies shut down production lines. And once they do, restarting them takes years. Geopolitics makes it worse. Brexit alone pushed UK antibiotic shortages from 648 in 2020 to over 1,600 in 2023. Supply chains that once moved drugs smoothly between Europe and the UK now face delays, tariffs, and paperwork. Meanwhile, over 85% of the world’s generic antibiotics come from just two countries: India and China. Any disruption there-whether it’s a factory fire, export ban, or currency crash-ripples across the globe.What’s Missing? The Drugs You Can’t Replace

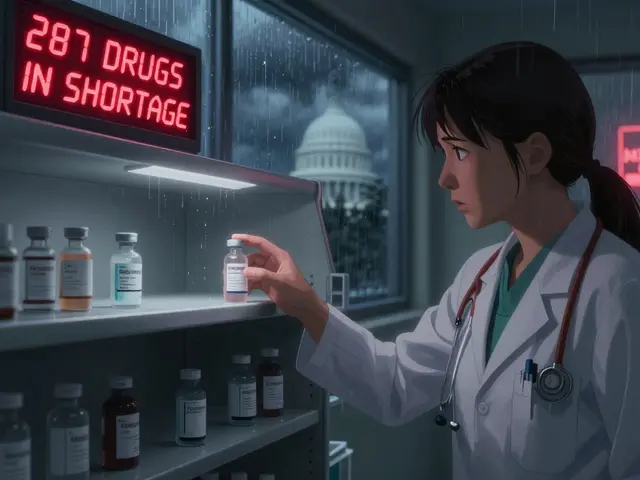

Not all drug shortages are equal. If you run out of a blood pressure pill, there are dozens of alternatives. But with antibiotics, you often have no backup. Take amoxicillin. It’s the first-line treatment for ear infections, pneumonia, and sinusitis in children. In January 2023, shortages hit the European Economic Area so hard that use of amoxicillin dropped by 55% and amoxicillin-clavulanate by 69%. Clinicians switched to broader-spectrum antibiotics like azithromycin or ceftriaxone. But those drugs are more expensive, harder to get, and push bacteria toward resistance faster. Even worse when third-generation cephalosporins vanish. Over 40% of E. coli and 55% of K. pneumoniae are now resistant to them. When those drugs disappear, doctors turn to carbapenems-antibiotics reserved for the most dangerous infections. Using them for routine cases? That’s like using a flamethrower to light a candle. It works, but it destroys the tool you need for real emergencies. In the U.S., 147 antibiotics were officially in shortage as of December 2024. Globally, 37 antimicrobials were listed as critically short by May 2024. Penicillin G benzathine has been unavailable since 2015. Colistin-a toxic, last-resort drug-is now being used for simple UTIs because nothing else is left.The Human Cost: When Treatment Isn’t an Option

Behind every shortage is a person waiting for medicine that never arrives. In California, Dr. Sarah Chen, an infectious disease specialist, told the American Public Health Association she had to give colistin to a patient with a routine urinary tract infection. Colistin can cause kidney failure. But with no alternatives, it was the only choice. In rural Kenya, a nurse described sending a child home with pneumonia because penicillin wasn’t in stock. The child died three days later. In Mumbai, a mother waited 72 hours for azithromycin to treat her child’s pneumonia. By the time it arrived, the infection had spread. The child ended up in intensive care. A 2025 survey of U.S. hospital pharmacists found that 78% had changed treatment plans because of shortages. 62% saw more patients develop complications-longer hospital stays, more ICU admissions, higher death rates. In low- and middle-income countries, the crisis is deeper. Already, 70% of antibiotics are inaccessible in these regions. Now, with global shortages, that number is climbing. The WHO calls this a “syndemic”-a deadly mix of under-treatment and rising resistance.

Why Resistance Is Getting Worse

Antibiotic shortages don’t just delay treatment-they make resistance worse. When a patient can’t get the right antibiotic, they might take a weaker one. Or they might take half a dose because there’s not enough to finish the course. Or they might use leftover antibiotics from a previous illness. All of these practices let bacteria survive, adapt, and multiply. The WHO’s 2025 surveillance report shows that between 2018 and 2023, resistance increased in over 40% of pathogen-antibiotic combinations. In the South-East Asian and Eastern Mediterranean regions, one in three infections is now resistant to first-line antibiotics. In Africa, it’s one in five. Professor Ramanan Laxminarayan put it plainly: “Overuse of ‘watch’ antibiotics and poor diagnostics accelerate global resistance.” When doctors don’t have fast tests to tell if an infection is bacterial or viral, they guess. And guess what? They guess wrong-and prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily. That’s another driver of resistance.What’s Being Done? The Gaps Between Plans and Reality

There are plans. There are reports. There are funding promises. The WHO announced a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative in October 2025, aiming to stabilize production by 2027. The European Commission is pushing new rules to guarantee minimum stockpiles. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing plants in January 2025, expected to cover 15% of current shortages by late 2025. But here’s the problem: these fixes are too slow, too small, and too focused on the wrong things. The U.S. spends billions on new antibiotic research, but almost nothing on manufacturing. The global antibiotic market grew just 1.2% from 2019 to 2024-far below the 5.7% average for all drugs. Why? Because no one wants to invest in something that doesn’t make money. Even when hospitals try to manage shortages, they’re overwhelmed. A 2025 APHA survey found 89% of U.S. hospitals had to ration antibiotics. 76% reported problems switching to alternatives-side effects, allergies, dosing errors. Pharmacists are working 22% longer just to keep up. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals meet the WHO’s full standards for antimicrobial stewardship programs. That means most don’t have the tools to track usage, predict shortages, or choose the right drug when supply is low.

What Works? Real Solutions on the Ground

Some places are finding ways to survive. In California, 12 hospitals created a regional antibiotic-sharing network in 2024. If one hospital runs out of vancomycin, another can send it overnight. The program cut critical shortage impacts by 43%. Johns Hopkins Hospital used rapid diagnostic tests to identify infections within hours-not days. That meant they could avoid broad-spectrum antibiotics unless absolutely necessary. They reduced unnecessary use by 37% during shortages. In New Zealand, where I’m based, hospitals have started using digital dashboards to track inventory in real time. When a drug drops below a week’s supply, alerts go out. Pharmacies coordinate with regional suppliers. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than waiting for a crisis. The key? Collaboration. Transparency. And treating antibiotic access like a public health emergency-not a market problem.The Future Is Bleak Unless We Act Now

Without major changes, the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts antibiotic shortages will increase by 40% by 2030. That could mean 1.2 million extra deaths every year from infections we used to treat in minutes. The WHO wants 70% of antibiotic use to come from the ‘Access’ group-safe, effective, low-cost drugs. Right now, it’s only 58%. We’re moving backward. Industry analysts expect a 22% increase in antibiotic development funding by 2027. That’s good news-if those new drugs can actually be made. But building factories takes years. Training workers takes longer. And right now, the factories that make the drugs we need are shutting down. This isn’t a future threat. It’s happening now. In hospitals. In clinics. In homes. The next time you hear about a drug shortage, don’t think of it as a supply chain glitch. Think of it as a warning. Antibiotics are not just medicine. They’re the last line of defense against a world where even a scraped knee could kill you.Why are antibiotics more likely to be in short supply than other drugs?

Antibiotics are cheaper to produce and sell than most other medications, especially generics. Manufacturers make so little profit that they stop making them. At the same time, production requires strict sterile conditions, which are expensive to maintain. When demand drops or costs rise, companies shut down lines-and restarting them takes years. Unlike cancer drugs or diabetes meds, antibiotics aren’t profitable, so they’re the first to disappear.

What happens when a hospital runs out of a common antibiotic like amoxicillin?

Doctors have to switch to broader-spectrum antibiotics like azithromycin or ceftriaxone. These drugs kill more types of bacteria, but they also destroy helpful bacteria in the body and increase the risk of resistance. Patients may get side effects like diarrhea or yeast infections. In children, delays can turn a simple ear infection into a hospital stay. In some cases, no good alternative exists, and patients are sent home untreated.

Are antibiotic shortages worse in poor countries?

Yes. In low- and middle-income countries, 70% of antibiotics are already inaccessible. Global shortages make it worse. These regions rely on imported generics, and when supply chains break down, there are no backups. Many clinics lack refrigeration, storage, or even basic diagnostics. A child with pneumonia may wait days for medicine that never arrives. In wealthier nations, shortages cause delays. In poorer ones, they cause death.

Can we just make more antibiotics?

It’s not that simple. Building a new manufacturing facility for sterile injectables costs over $100 million and takes 3-5 years. Even if funding were available, most companies won’t invest because antibiotics don’t make money. The market is flooded with cheap generics from India and China. Profit margins are razor-thin. Without government subsidies, price guarantees, or guaranteed purchases, no manufacturer will take the risk.

What can I do as a patient to help?

Don’t pressure your doctor for antibiotics. If they say you have a virus, trust them. Don’t save leftover antibiotics for later. Don’t take someone else’s prescription. Ask if there’s a generic version available. Support policies that fund antibiotic production and stewardship programs. And if you’re a healthcare worker, advocate for better tracking and sharing systems in your hospital. Everyone has a role in preventing this crisis from getting worse.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us