When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might think it’s just a cheaper copy. But behind every generic pill is a rigorous scientific process designed to prove it works exactly like the brand-name version. That process is called a bioequivalence study. These aren’t just lab tests-they’re tightly controlled clinical trials involving real people, precise measurements, and strict statistical rules. If the study fails, the generic drug doesn’t get approved. And if it passes, you can trust it to do the same job as the expensive original.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Exist

Bioequivalence studies exist because regulators don’t require generic drug makers to repeat full clinical trials. Instead, they need to prove the generic delivers the same active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same speed and amount as the brand-name drug. This is based on a simple but powerful idea: if the body absorbs the drug the same way, the effect will be the same. This approach started in the U.S. with the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic manufacturers had to run expensive, time-consuming clinical trials. The law changed that, opening the door for affordable medicines. Today, the FDA estimates generics saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.6 trillion between 2010 and 2019. Similar systems exist in Europe, Japan, Canada, and elsewhere. Without bioequivalence studies, most generics wouldn’t be legal.The Core Design: Crossover Study

The most common way to run a bioequivalence study is a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. Here’s how it works:- 24 to 32 healthy volunteers sign up (sometimes up to 100 for tricky drugs).

- Half get the generic drug first, then the brand-name after a break.

- The other half get the brand-name first, then the generic.

- There’s a washout period between doses-usually at least five half-lives of the drug. For a drug that clears in 12 hours, that’s 60 hours. For one with a 72-hour half-life, it’s over two weeks.

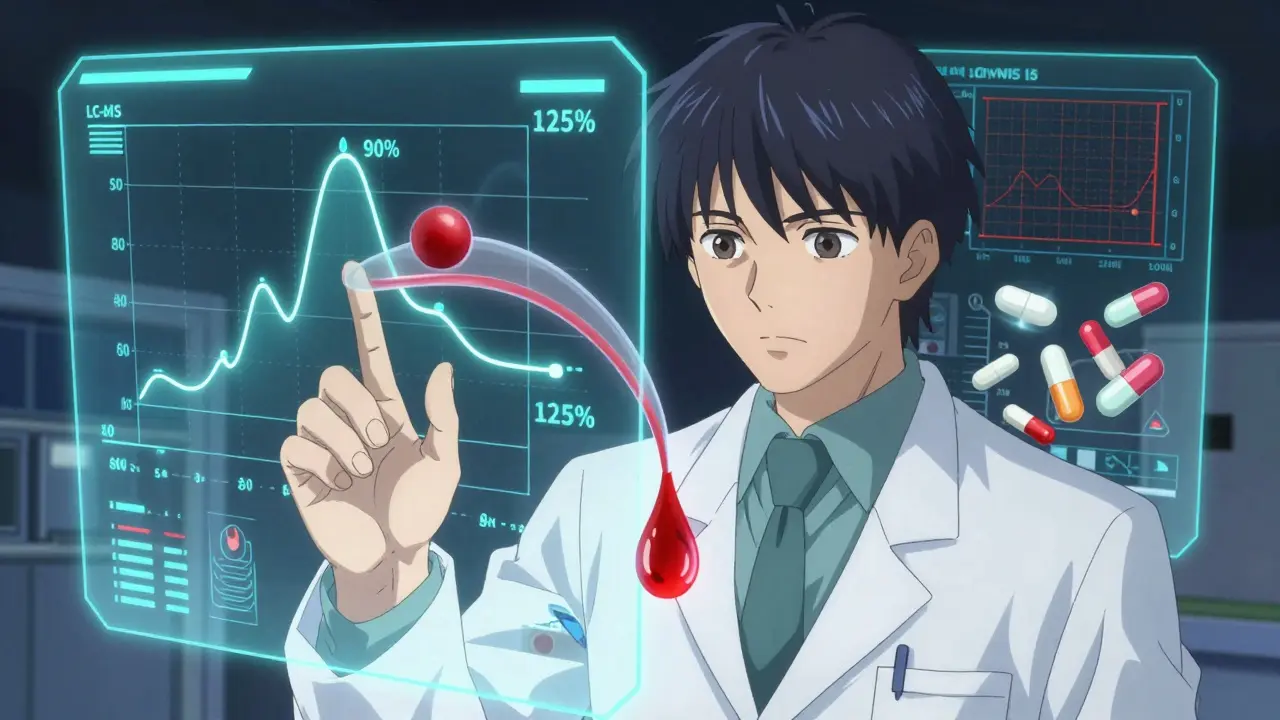

What’s Measured: Cmax and AUC

Blood samples are taken at specific times after each dose. At least seven time points are collected: before dosing, around the peak concentration (Cmax), and several during the elimination phase. Sampling continues until at least 80% of the total drug exposure (AUC∞) is captured-usually 3 to 5 half-lives. Two numbers are critical:- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug gets absorbed.

- AUC(0-t): The total amount of drug absorbed over time. This tells you how much of the drug gets into the system.

How the Data Is Analyzed

The raw concentration numbers are log-transformed. Why? Because drug levels in blood don’t change linearly-they follow a curve. Log transformation makes the math work properly. Then, a statistical model called ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) is used. It accounts for:- Sequence (who got which drug first)

- Period (first or second dose)

- Treatment (generic vs. brand)

- Subject (individual differences)

Special Cases: Highly Variable and Complex Drugs

Not all drugs behave the same. Some have high variability-meaning the same person’s blood levels can jump around a lot from dose to dose. For these, the standard 80-125% rule doesn’t work well. The EMA handles this with replicate designs: four-period studies where each subject gets the reference and test products multiple times. This gives more data to account for variability. The FDA allows a method called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the brand drug is. For drugs with long half-lives (like some antidepressants or antivirals), a crossover study isn’t practical. A parallel design is used instead-two separate groups, one gets the generic, the other the brand. But this requires more subjects (often 80-100) to get reliable results. Modified-release drugs (slow-release pills) need multiple-dose studies. Instead of one dose, subjects take the drug daily for several days. This checks if the drug builds up correctly in the body over time.The Analytical Side: LC-MS/MS and Validation

Measuring drug levels in blood isn’t easy. You’re looking for nanograms per milliliter in a sea of proteins, fats, and other chemicals. That’s why labs use LC-MS/MS-liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. It’s precise, sensitive, and reliable. But the method must be validated. That means proving it’s accurate, repeatable, and stable. Precision must be within ±15% (±20% at the lowest detectable level). If the lab’s method isn’t validated properly, the whole study can be thrown out. BioAgilytix’s 2023 white paper found that 22% of bioequivalence studies face delays due to analytical issues. One mistake in calibration or sample handling can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and months of time.What the Test Product Must Be

The generic drug tested isn’t just any batch-it has to represent what will be sold commercially. The EMA requires it to come from a batch that’s at least 1/10th of full production scale or 100,000 units, whichever is larger. The FDA expects the same. The reference product? It’s usually a single batch of the brand-name drug. Regulators prefer the batch with an intermediate dissolution profile-not the fastest or slowest. This ensures the comparison reflects real-world performance. Dissolution testing is also required. The generic and brand must release the drug similarly across different pH levels (from stomach acid to intestine). The f2 similarity factor must be above 50, tested on at least 12 units per profile. If the dissolution curves don’t match, the study fails-even if blood levels look fine.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Based on FDA data, the top reasons bioequivalence studies fail:- 45%: Inadequate washout period-subjects still have leftover drug in their system from the first dose.

- 30%: Poor sampling schedule-missing the Cmax or not sampling long enough to capture full AUC.

- 25%: Statistical errors-wrong model, wrong transformation, or misinterpretation of confidence intervals.