When a generic drug hits the market, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it works the same way in your body? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab terms-they’re the foundation of everything that makes a generic drug safe and effective.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It tells you the highest level of a drug in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a wave-the moment the drug hits its strongest point. For some drugs, that peak matters a lot. If you’re taking painkillers, for example, you want that peak to be high enough to relieve pain fast. But if the drug has a narrow safety window-like warfarin or lithium-too high a peak could be dangerous.

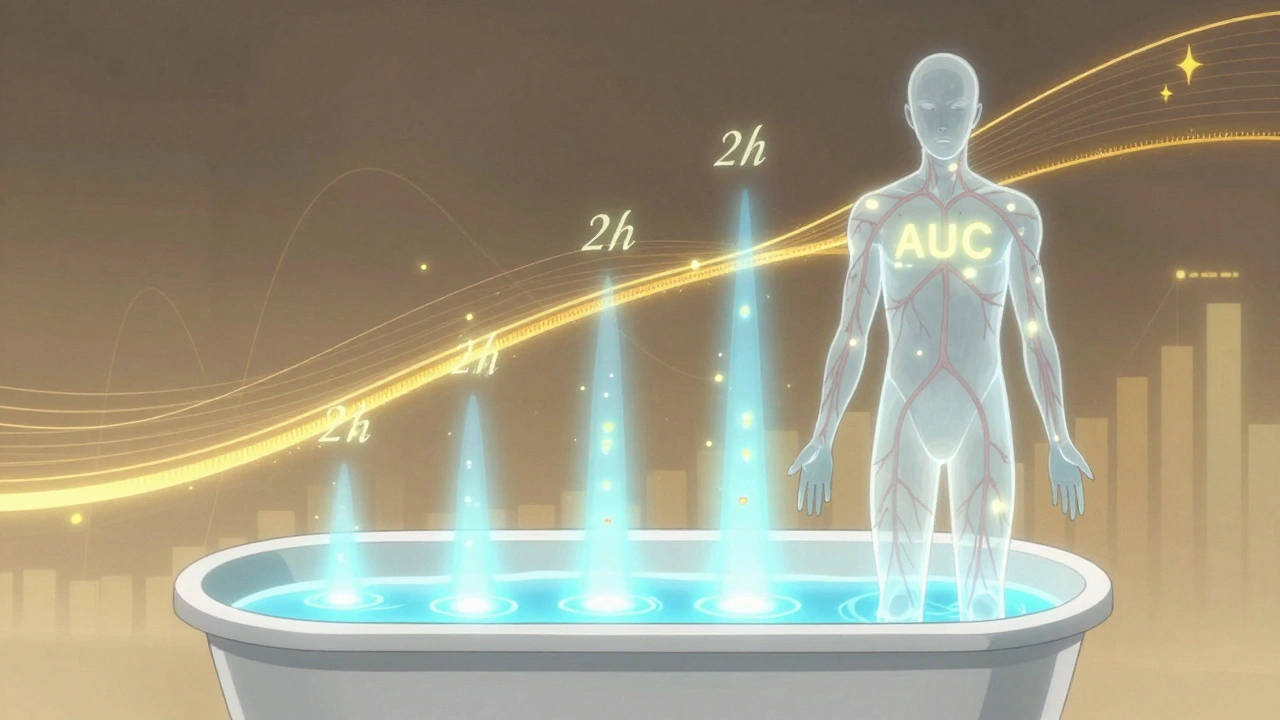

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total exposure. It’s the entire area under the graph of drug concentration over time. Imagine pouring water into a bathtub. Cmax is how high the water gets at its highest point. AUC is how much water ended up in the tub over the whole time. It tells you how much of the drug your body absorbed overall. For drugs that work over hours-like antibiotics or blood pressure meds-AUC is often more important than the peak.

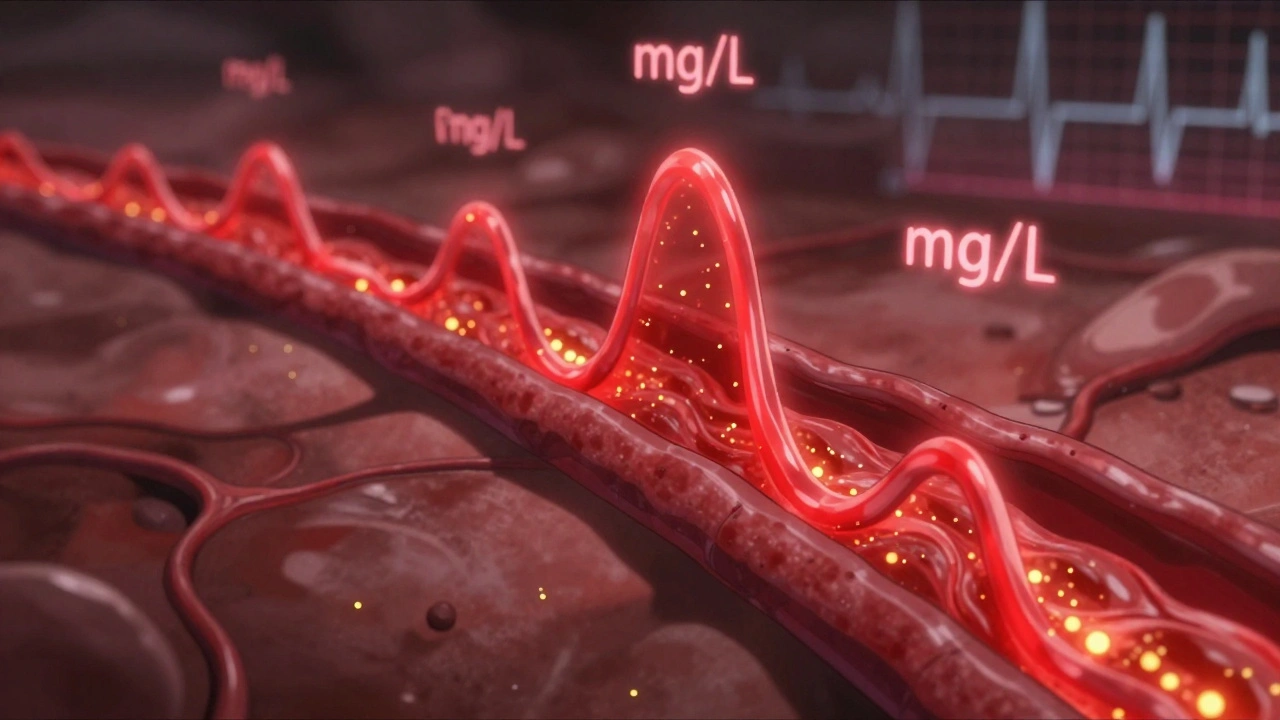

Both numbers are measured in real units: Cmax in mg/L, AUC in mg·h/L. These aren’t guesses. They come from blood samples taken every 15 to 60 minutes after a dose, tracked over 24 to 72 hours. Modern labs use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which can detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s like finding a single grain of salt in an Olympic-sized pool.

Why Both Numbers Are Non-Negotiable

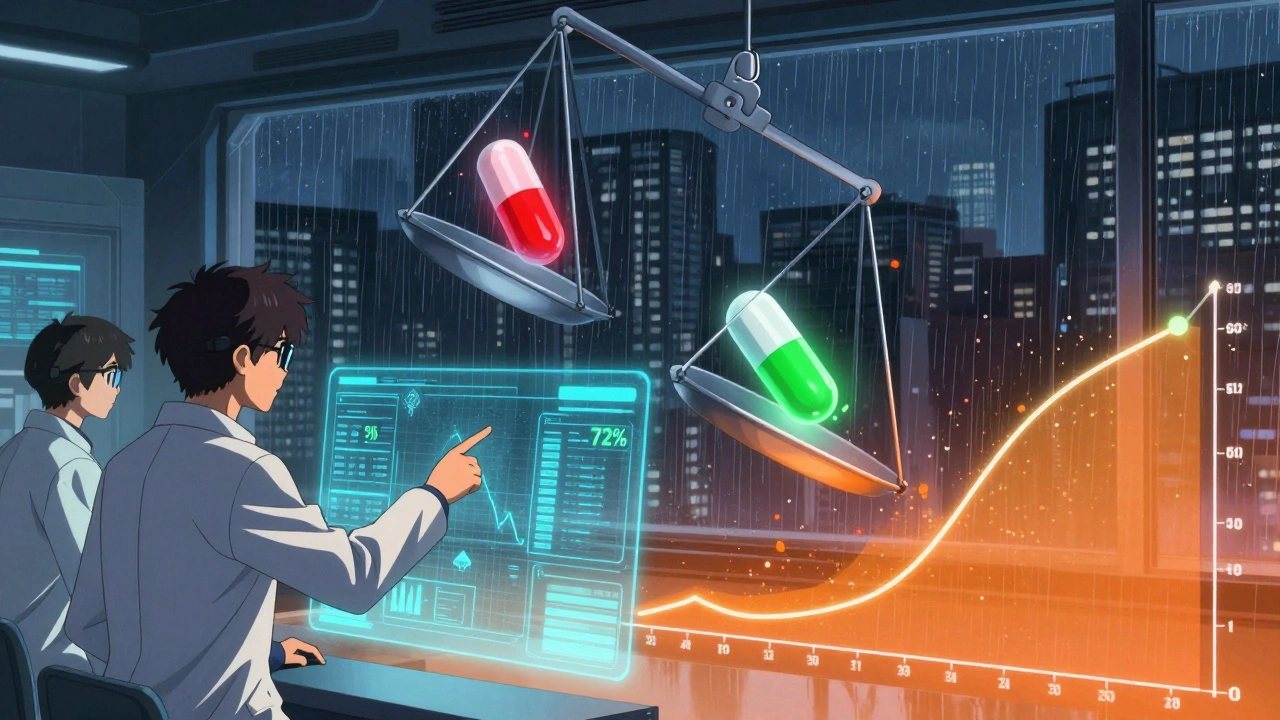

Regulators don’t just check one number. They demand both Cmax and AUC pass the same strict test. The rule? The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand drug gives you a Cmax of 10 mg/L, the generic must deliver between 8 and 12.5 mg/L. Same for AUC.

This range didn’t come out of nowhere. It was set in the early 1990s after years of clinical data showed that differences smaller than 20% rarely caused real-world problems. On a log scale, ln(0.8) = -0.2231 and ln(1.25) = 0.2231-perfectly symmetrical. That’s why statisticians use log-transformed data: because drug concentrations don’t follow a normal bell curve. They follow a log-normal one.

And here’s the kicker: both numbers must pass. If the AUC ratio is 95% but Cmax is 75%, the drug fails. No exceptions. That’s because Cmax tells you about how fast the drug gets into your system, and AUC tells you about how much gets in. One without the other is incomplete. A drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but hit peak levels too quickly-leading to side effects-or too slowly-making it ineffective.

How Studies Are Done

Testing isn’t done on patients. It’s done on healthy volunteers-usually 24 to 36 people. Each person takes both the brand and generic versions, in random order, with a washout period in between. This is called a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. It cancels out individual differences in metabolism.

Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over several days. The first few samples are critical. If you miss the early time points-say, you only check at 1, 2, and 4 hours-you might miss the true Cmax. Industry data shows that poor sampling in the first 1-2 hours causes about 15% of bioequivalence studies to fail. That’s why guidelines say: use actual sampling times, not scheduled ones. If a sample was taken at 1.8 hours, you don’t pretend it was at 2.0.

Analysis is done with specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin. The raw data gets log-transformed, ratios are calculated, confidence intervals are built, and then the verdict comes: pass or fail. Most studies take 2-3 days to process after all samples are in.

When the Rules Get Tighter

For most drugs, 80%-125% is fine. But for some, it’s not enough. Drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, cyclosporine, and phenytoin have narrow therapeutic indexes. That means a tiny change in exposure can mean the difference between no effect and toxicity.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) says for these, tighter limits-90% to 111%-may be needed. The FDA hasn’t adopted this universally, but it’s open to case-by-case requests. In 2022, a study of 500 bioequivalence trials found that while 82% of generics matched the brand within 90%-110% for AUC, only 78% did for Cmax. That small gap matters for high-risk drugs.

There’s another twist: highly variable drugs. Some people metabolize them wildly differently. If a drug’s variability within a person is over 30%, the 80%-125% rule can unfairly reject good generics. That’s why the EMA allows something called scaled average bioequivalence-it widens the range based on how variable the drug is. The FDA does something similar. But it’s not automatic. It requires extra data and justification.

What Happens When Bioequivalence Fails

It happens more than you think. In 2022, the FDA approved over 1,200 generic drugs. But hundreds more were rejected or sent back for more data. Common reasons? Inadequate sampling, poor study design, or Cmax/AUC ratios outside the window.

One case from 2020 involved a generic version of a popular statin. The AUC was fine-97% of the brand. But Cmax was 72%. Why? The generic used a different filler that slowed absorption. The peak was lower and delayed. Patients might not feel the full effect early in the day. The company had to reformulate and retest.

That’s why bioequivalence isn’t just paperwork. It’s about real people. A generic that fails Cmax might not cause harm right away, but over time, inconsistent absorption can lead to poor control of chronic conditions-higher blood pressure, more seizures, unstable thyroid levels.

The Bigger Picture

Bioequivalence testing saves billions. Without it, every generic would need expensive clinical trials-testing for heart attacks, strokes, or survival rates. Instead, we rely on Cmax and AUC as proven surrogates. Decades of data show that if two drugs have similar exposure and peak levels, they work the same way in the body.

A 2019 meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine looked at 42 studies comparing generics and brand-name drugs. It found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness when bioequivalence criteria were met. That’s why 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are now for generics.

But the science is evolving. For complex drugs-like extended-release pills that release in stages-the standard AUC and Cmax might not capture everything. The FDA is now exploring partial AUC (e.g., AUC from 0-4 hours) for these cases. Modeling and simulation might one day reduce the need for human studies. But for now, Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard.

And they will for years to come. As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said at a 2022 conference: “AUC and Cmax have been validated over three decades. They’re not perfect, but they’re reliable. And for most drugs, that’s enough.”

What This Means for You

If you’re prescribed a generic, you can trust it. The system works. Regulators didn’t just pick numbers out of a hat. They built them on real science, real data, and real patient outcomes.

But if you notice a change in how you feel after switching-more side effects, less relief-don’t ignore it. Talk to your doctor. It’s rare, but sometimes individual sensitivity matters. And if your drug has a narrow therapeutic index, your pharmacist might even check if the generic you got passed the tighter 90%-111% range.

Behind every pill you take is a story of chemistry, statistics, and regulation. Cmax and AUC are the unsung heroes of that story.

What does Cmax tell you about a drug?

Cmax tells you the highest concentration of a drug in your bloodstream after you take it. It reflects how quickly the drug is absorbed. For drugs where timing matters-like painkillers or seizure meds-Cmax helps ensure you get relief fast. For drugs with narrow safety margins, like warfarin, a Cmax that’s too high can cause dangerous side effects.

Why is AUC more important than Cmax for some drugs?

AUC measures total drug exposure over time. For drugs that need steady levels-like antibiotics, blood pressure meds, or antidepressants-how much drug your body gets over 24 hours matters more than when it peaks. AUC ensures you’re getting enough to work, even if absorption is slow.

Why do regulators require both Cmax and AUC?

Because they measure different things. Cmax tells you about the rate of absorption; AUC tells you about the extent. A drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) as the brand but absorb too slowly or too fast, changing how it works. Both must meet the 80%-125% range for a generic to be approved.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

It’s not approved. The manufacturer must fix the formulation-change the ingredients, particle size, or coating-and run the study again. Many generics fail the first time, especially if they use different excipients. This ensures only safe, effective versions reach the market.

Are there drugs that need tighter bioequivalence limits?

Yes. Drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes-like levothyroxine, warfarin, cyclosporine, and phenytoin-can cause serious harm from small exposure changes. The EMA recommends 90%-111% limits for these. The FDA considers them case by case. Even a 10% difference can affect thyroid levels or blood clotting.

Can I trust a generic drug that passed bioequivalence testing?

Yes. Over 1,200 generic drugs are approved in the U.S. each year using these standards. A major 2019 study found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that passed bioequivalence. The system is strict, well-tested, and protects patients.

Do Cmax and AUC apply to all types of drugs?

They’re the standard for most oral drugs. But for complex formulations-like extended-release pills or patches-the standard AUC and Cmax may not capture everything. Regulators are now exploring partial AUC or other metrics. For now, though, they remain the baseline for nearly all generic approvals.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us