DIL Medication Risk Checker

Check Your Medication Risk

Select your medication to determine if it's associated with Drug-Induced Lupus (DIL), along with typical symptoms and recovery timeline.

When a pill you trust starts attacking your own tissues, the experience can be terrifying. Drug‑Induced Lupus is a reversible autoimmune reaction that looks a lot like classic lupus but usually disappears once the culprit drug is stopped.

Key Takeaways

- Symptoms appear weeks to months after starting a high‑risk medication.

- Positive ANA and anti‑histone antibodies are the hallmark lab clues.

- Stopping the offending drug leads to improvement in 80 % of patients within 4 weeks.

- Only a minority need short‑term NSAIDs or low‑dose steroids.

- Genetic factors such as HLA‑DR4 and NAT2 slow‑acetylator status raise the risk.

What is Drug‑Induced Lupus?

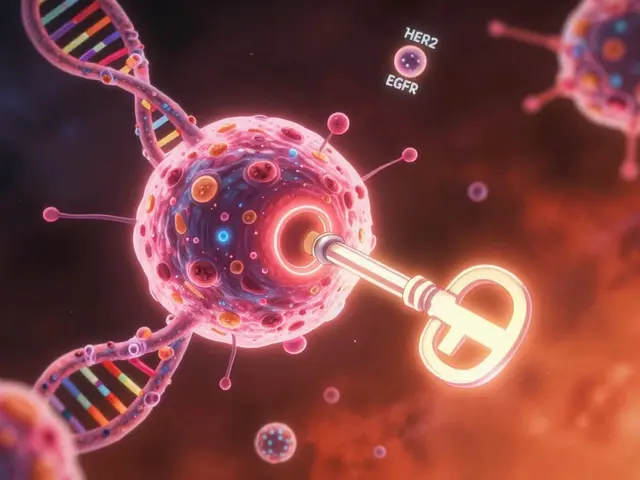

Drug‑Induced Lupus (DIL) is an autoimmune disorder triggered by certain medications. The immune system mistakenly creates antibodies that attack healthy cells, producing fever, joint pain, muscle aches, and sometimes inflammation around the lungs or heart. Unlike idiopathic systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), DIL rarely harms the kidneys or brain, and symptoms typically fade after the drug is withdrawn.

The condition was first noticed in the 1950s when patients on the hypertension drug hydralazine started complaining of lupus‑like complaints. Since then, more than 80 % of DIL cases resolve completely within weeks to months of drug cessation.

How DIL Differs from Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Feature | Drug‑Induced Lupus | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

|---|---|---|

| Typical age at onset | ≥ 50 years (both genders) | 15‑45 years, female‑predominant (9:1) |

| Gender distribution | ≈ 1:1 | ≈ 9:1 (female) |

| Common offending drugs | Hydralazine, Procainamide, TNF‑α inhibitors, Pembrolizumab | Not drug‑related |

| ANA positivity | 95 %+ | 95 %+ |

| Anti‑histone antibodies | 75‑90 % | 50‑70 % |

| Anti‑dsDNA antibodies | <10 % | 60‑70 % |

| Renal involvement | <5 % | 30‑50 % |

| CNS involvement | <3 % | 20‑30 % |

| Resolution after drug stop | 80‑95 % within 12 weeks | Chronic, lifelong |

Typical Symptoms to Watch For

While every patient’s story is unique, research shows a fairly consistent symptom pattern:

- Muscle pain (75‑85 % of cases)

- Joint pain with swelling (65‑75 %)

- Fever and unexplained fatigue (50‑90 %)

- Weight loss (30‑40 %)

- Serositis - pleuritis or pericarditis (25‑35 %)

- Photosensitivity (20‑30 %) - less common than in SLE

- Malar rash - occurs in only 10‑15 % of DIL patients

Major organ damage such as lupus nephritis or severe neuro‑psychiatric disease is rare, which is a key clue that the lupus‑like picture may be drug‑induced.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Age and gender are the first clues - most diagnoses happen after age 50 and affect men and women equally. The real risk drivers are the drugs themselves and the patient’s genetics.

High‑risk medications

- Procainamide - up to 30 % incidence with long‑term use

- Hydralazine - 5‑10 % incidence, especially in slow acetylators

- Minocycline, anti‑TNF agents, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) - 1‑3 % incidence

Genetic predisposition

People carrying the HLA‑DR4 allele have a 3.2‑fold higher chance of DIL. Slow‑acetylator status for the NAT2 enzyme raises hydralazine‑related risk by about 4.7‑fold.

Testing and Diagnosis

Because DIL mimics many other conditions, a systematic approach saves time and prevents unnecessary immunosuppression.

- Medication history - Review every prescription, over‑the‑counter product, and supplement started within the past 24 months.

- ANA screen - Positive in >95 % of DIL; a diffuse speckled pattern is typical.

- Anti‑histone antibody assay - Positive in 75‑90 % of cases, especially with hydralazine or procainamide.

- Anti‑dsDNA and complement levels - Usually normal or only mildly reduced, helping to rule out SLE.

- Inflammatory markers - ESR elevated in 60‑70 %; CRP modestly raised in 40‑50 %.

- Exclude other diseases - Imaging, urinalysis, and neurologic work‑up are reserved for atypical presentations.

If several drugs could be responsible, a stepwise withdrawal protocol is recommended: stop the most likely agent, monitor labs and symptoms for 8-12 weeks, then move to the next suspect if needed.

Management and Recovery

The cornerstone of treatment is simply stopping the offending medication. Here’s what the evidence says about what to expect:

- Improvement begins in 2-4 weeks for 80 % of patients.

- Complete symptom resolution occurs in 95 % within 12 weeks.

- For lingering joint pain, NSAIDs (ibuprofen 400‑600 mg TID) help 60‑70 % of mild cases.

- Moderate disease may need a short course of low‑dose prednisone (5‑10 mg daily for 4‑8 weeks), effective in 85‑90 %.

- Severe or organ‑threatening inflammation is rare but can be managed with azathioprine (2‑3 mg/kg/day) or methotrexate (10‑25 mg weekly).

Because the original drug was often prescribed for hypertension, arrhythmia, or autoimmune skin disease, clinicians must replace it with a safer alternative. For example, switching from procainamide to amiodarone cuts DIL risk from up to 30 % down to 0.1‑0.3 %.

Recovery Timeline at a Glance

| Week | What Usually Happens |

|---|---|

| 0‑2 | Fever and fatigue start to drop; joint swelling may persist. |

| 3‑4 | Most patients notice marked relief in muscle pain; labs show falling ESR. |

| 5‑8 | Anti‑histone antibodies begin to normalize; NSAIDs often no longer needed. |

| 9‑12 | Complete symptom resolution for >95 % of cases; ANA may remain faintly positive. |

| >12 | Long‑term follow‑up focuses on managing the condition that required the original drug. |

Preventing Future Episodes

Awareness and a few practical steps can keep DIL off the radar:

- Ask providers to review medication lists annually, especially for drugs with black‑box warnings.

- Consider pharmacogenetic testing for NAT2 before starting hydralazine in patients over 50.

- Prefer newer antihypertensives (e.g., ACE inhibitors) over high‑risk agents when possible.

- Monitor ANA and anti‑histone titers after initiating a known culprit, especially in genetically susceptible individuals.

Quick Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- Identify any new medication started within the past 3‑24 months.

- Ask about joint, muscle, or chest pain, fever, and unexplained fatigue.

- Order ANA and anti‑histone antibody tests.

- If positive, discontinue the suspect drug and observe for improvement.

- Use NSAIDs or short‑course steroids only if symptoms persist beyond 4 weeks.

- Document recovery and plan for an alternative therapy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can drug‑induced lupus become permanent?

In the overwhelming majority of cases, symptoms disappear once the offending drug is stopped. Persistent disease is rare and usually signals an undetected co‑existing autoimmune condition.

How long does it take for lab tests to return to normal?

Anti‑histone antibodies often normalize within 2‑3 months, while ANA may stay low‑positive for years without clinical significance.

Are over‑the‑counter supplements a risk?

Some herbal products contain compounds that can trigger lupus‑like reactions, especially in people already taking high‑risk prescription drugs. Always discuss supplements with your doctor.

Should I get genetic testing before starting hydralazine?

Guidelines in Europe recommend NAT2 genotyping for patients over 50. In the U.S. it’s optional but can help avoid DIL in slow acetylators.

What if my doctor can’t find an alternative medication?

In rare cases the benefit of the original drug outweighs the DIL risk. A rheumatologist may then prescribe a low‑dose steroid or immunomodulator to keep the autoimmune reaction under control while you stay on the essential medication.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us