When two drugs are taken together, they don’t just sit side by side in your body. They talk to each other-sometimes helping, sometimes hurting. This isn’t about one drug changing how the other is absorbed or broken down. That’s pharmacokinetics. This is about what happens at the target site: the receptors, the nerves, the organs where the drugs actually do their work. This is pharmacodynamic interaction, and it’s responsible for nearly half of all serious drug-related hospitalizations.

How Drugs Talk at the Receptor Level

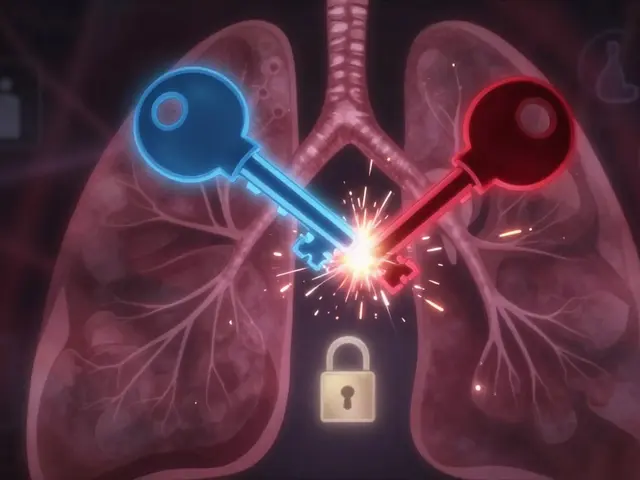

Think of your body’s receptors as locks. Drugs are keys. When a drug fits into a lock, it turns it-triggering a response. Sometimes, two drugs try to use the same lock. One might be a strong key that fits perfectly. The other might be a weak one that barely turns the lock. If they’re both present, the stronger key wins. That’s receptor competition. A classic example is albuterol and propranolol. Albuterol opens up airways in asthma patients by activating beta-2 receptors. Propranolol, a beta-blocker used for high blood pressure or heart rhythm issues, blocks those same receptors. If someone on propranolol takes albuterol during an asthma attack, the propranolol can stop the albuterol from working. The result? No relief. Worse, it can turn a manageable flare-up into a life-threatening event. The key here is affinity-the strength with which a drug binds to its receptor. Drugs with higher affinity (measured in nanomolar ranges) dominate. This isn’t about dose alone. It’s about molecular fit. Even a small amount of a high-affinity blocker can shut down the effect of a much larger dose of a weaker agonist.Additive, Synergistic, and Antagonistic Effects

Not all interactions are bad. They fall into three clear categories:- Additive: The combined effect equals the sum of each drug alone. Taking acetaminophen and ibuprofen together for pain gives you roughly the total effect of both drugs individually.

- Synergistic: Together, they do more than the sum. Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) work this way. They block two different steps in bacterial folic acid production. Alone, each needs high doses. Together, they’re powerful at low doses-cutting the needed amount by 75% and reducing side effects.

- Antagonistic: One drug cancels or reduces the other. This is where things get dangerous. Opioid antagonists like naloxone can reverse an overdose by kicking morphine off opioid receptors. But if someone is physically dependent on opioids, giving naloxone too fast can trigger violent withdrawal-seizures, vomiting, spikes in blood pressure.

When Drugs Interfere With Your Body’s Natural Balance

Not all interactions happen at receptors. Sometimes, drugs mess with your body’s natural systems. Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen and ACE inhibitors like lisinopril. ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure by relaxing blood vessels. But they also rely on kidney prostaglandins to maintain blood flow to the kidneys. NSAIDs block those same prostaglandins. The result? A 25% drop in kidney blood flow, according to a 2019 NIH study. Blood pressure doesn’t drop as expected. Kidney function can decline. In older adults, this combo can trigger acute kidney injury. Another example: diuretics (water pills) and NSAIDs. Diuretics help the body get rid of fluid. NSAIDs reduce kidney blood flow. Together, they can cause dangerous fluid and electrolyte imbalances-low sodium, high potassium. That’s why doctors often avoid giving these together to patients with heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

Why Some Combinations Are Far More Dangerous Than Others

Not all drugs are created equal. The danger spikes when one or both drugs have a narrow therapeutic index-meaning the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny. Drugs like warfarin, digoxin, lithium, and phenytoin all fall into this category. Their therapeutic index is below 3.0. A small change in effect can mean the difference between control and crisis. A 2019 NIH analysis found that 83% of life-threatening pharmacodynamic interactions involved at least one of these drugs. For example, combining warfarin with an NSAID doesn’t just increase bleeding risk-it can push INR levels into dangerous territory overnight. The NSAID doesn’t change warfarin’s concentration. It changes how the body responds to it-by weakening blood vessel walls and interfering with platelet function. The same goes for CNS depressants. Combining benzodiazepines, opioids, and alcohol? Each one slows breathing a little. Together, they can shut it down. A 2020 FDA analysis showed 68% of serious adverse events from pharmacodynamic interactions led to hospitalization-compared to 42% for pharmacokinetic ones.How Clinicians Spot and Avoid These Interactions

Doctors and pharmacists don’t guess. They use tools. The NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service tracks over 1,800 pharmacodynamic interactions. Of those, 287 are flagged as “potentially harmful and contraindicated.” That’s not a suggestion. That’s a red light. Electronic health records now include clinical decision support systems. These flag dangerous combos before the prescription is even printed. A 2020 study across 48 U.S. hospitals found these systems cut errors by 37%. But they still miss 22%-because they’re programmed to look for known patterns. They don’t always catch rare or complex interactions. The most effective defense? Pharmacist-led medication reviews. A 2021 BMJ study showed that when pharmacists sit down with elderly patients and go through every pill, they reduce adverse events from pharmacodynamic interactions by 58%. The top two preventable combos? Antihypertensives with NSAIDs, and multiple sedatives.

When Interactions Work for You

Pharmacodynamic interactions aren’t always the enemy. Sometimes, they’re the solution. Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) is being studied for depression, chronic pain, and autoimmune conditions. It’s usually an opioid blocker. But at very low doses, it may temporarily block opioid receptors, causing the body to produce more endorphins. When paired with antidepressants, a 2021 study found 68% of patients with treatment-resistant depression improved-compared to 42% on antidepressants alone. Another example: combining beta-blockers with diuretics for high blood pressure. The beta-blocker reduces heart rate and output. The diuretic reduces fluid volume. Together, they work better than either alone-and often with fewer side effects than higher doses of one drug. The key is intention. These aren’t accidents. They’re designed combinations based on deep understanding of how drugs interact at the physiological level.What You Can Do

If you’re taking more than three medications, you’re at higher risk. Here’s how to protect yourself:- Keep a written list of every drug you take-including over-the-counter pills, supplements, and herbal products.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Are any of these drugs known to interact with each other?” Don’t assume the doctor knows every combo.

- If you start a new medication, watch for sudden changes: dizziness, confusion, swelling, unusual fatigue, or mood shifts.

- Never stop or change a dose without talking to your provider-especially with drugs like warfarin, lithium, or seizure medications.

- Use one pharmacy for all your prescriptions. They can track interactions across all your meds.

The Future: Smarter, Predictive Systems

The field is moving fast. The FDA now requires pharmacodynamic interaction studies for all new CNS drugs. The European Medicines Agency saw a jump from 19% to 34% of new drug applications including this data between 2015 and 2022. Researchers are building machine learning models that predict interactions before they happen. Dr. Rada Savic’s team at UCSF developed an algorithm that predicts serotonin syndrome risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing patient profiles, drug doses, and genetic factors. The UK’s NHS is piloting real-time alerts in electronic records that flag dangerous combos as prescriptions are written. Imagine getting a warning before you even leave the pharmacy: “This combo may cause dangerous drops in blood pressure. Consider alternatives.” By 2050, 1.5 billion people will be over 65-and on average, each will be taking nearly five prescription drugs. Pharmacodynamic interactions won’t disappear. But with better tools, better education, and better communication, we can stop them from harming people.What’s the difference between pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug interactions?

Pharmacokinetic interactions change how your body handles the drug-like how fast it’s absorbed, broken down, or cleared. For example, grapefruit juice slows down liver enzymes that break down statins, causing higher blood levels. Pharmacodynamic interactions happen at the target site: the drug changes how another drug works at its receptor or in its physiological effect-without changing the drug’s concentration. Propranolol blocking albuterol’s effect on lungs is pharmacodynamic. Grapefruit juice affecting statin metabolism is pharmacokinetic.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause dangerous pharmacodynamic interactions?

Absolutely. Ibuprofen, naproxen, and other NSAIDs can reduce the effectiveness of blood pressure medications like ACE inhibitors or diuretics. Antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can add to sedation when taken with opioids or benzodiazepines. Even herbal supplements like St. John’s wort can interfere with antidepressants by altering serotonin pathways. What seems harmless can be risky when combined with prescription drugs.

Why are elderly patients more at risk for pharmacodynamic interactions?

Older adults often take multiple medications for chronic conditions-average of 4.8 prescriptions. Their bodies process drugs differently: kidney and liver function decline, body fat increases, and receptor sensitivity changes. A drug that was safe at 50 can become dangerous at 75. Also, they’re more likely to be on drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, like warfarin or digoxin, where tiny changes in effect can cause harm.

Are pharmacodynamic interactions always obvious?

No. Many are subtle. Blood pressure might drop a little more than expected. Pain relief might be weaker. A mood stabilizer might seem less effective. Symptoms can be mistaken for disease progression or aging. That’s why regular medication reviews with a pharmacist are critical-especially if you’ve recently started or stopped a drug.

Can pharmacodynamic interactions be reversed?

Sometimes. If the interaction is antagonistic-like a beta-blocker blocking an asthma drug-the solution is to stop the blocker or switch to a different type. In cases of serotonin syndrome, stopping the drugs and giving supportive care (fluids, cooling, benzodiazepines) can reverse symptoms. For opioid overdose, naloxone can quickly reverse the effect. But not all interactions are reversible. Sometimes, the damage-like kidney injury from NSAIDs and ACE inhibitors-can be permanent.

Understanding pharmacodynamic interactions isn’t just for doctors. It’s for anyone taking more than one medication. The right knowledge can prevent a hospital visit-or save a life.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us