When doctors combine gabapentinoids like gabapentin or pregabalin with opioids for pain control, they’re trying to do two things: reduce the amount of opioids needed and improve pain relief. It sounds smart - and for years, it was widely used, especially after surgery. But the reality is more dangerous than many patients and even some clinicians realize. The combination doesn’t just add up - it multiplies risk. And the biggest danger isn’t nausea or constipation. It’s respiratory depression.

Why This Combination Was Ever a Good Idea

Gabapentin and pregabalin were never meant to be painkillers. They were developed as antiseizure drugs. But doctors noticed something: patients with nerve pain - like diabetic neuropathy or post-surgical pain - felt better on them. So they started using them as add-ons to opioids. The theory was simple: if gabapentinoids can cut opioid needs by 20-30%, you reduce side effects like constipation, drowsiness, and addiction risk. For a while, it worked. Hospitals adopted protocols. Prescriptions soared. In the U.S., gabapentinoid use jumped 64% between 2012 and 2017. But here’s the problem: reducing opioid doses doesn’t mean reducing risk. It just shifts it.How Gabapentinoids Make Opioids More Dangerous

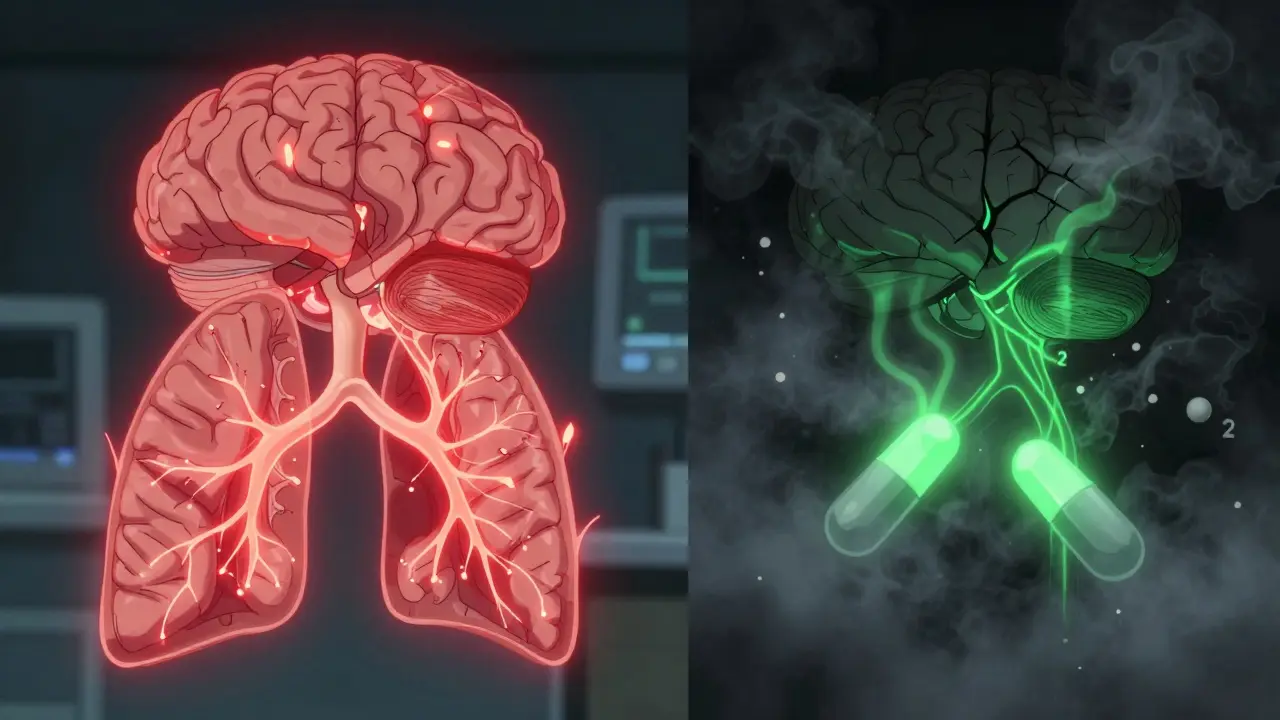

The danger isn’t just that both drugs make you sleepy. It’s that they attack breathing in different but deadly ways. Opioids slow down the brainstem - the part that tells your lungs to breathe. It’s why overdoses kill: the body stops breathing. Gabapentinoids don’t work the same way. They reduce the brain’s sensitivity to carbon dioxide. That means even when CO2 builds up in your blood - a signal that you need to breathe - your brain doesn’t respond as strongly. So you keep breathing slower and shallower, even when your body is screaming for air. And it gets worse. Opioids slow down your gut. That means gabapentinoids hang around longer in your intestines, getting absorbed more fully. One study found this boosts gabapentin levels by 44%. So you’re not just taking two sedating drugs - you’re taking a stronger version of one of them. Animal studies show gabapentin can even reverse opioid tolerance. That means someone who’s been on opioids for months might suddenly react like a first-time user. A dose that was safe last week becomes dangerous this week.Who’s at Highest Risk?

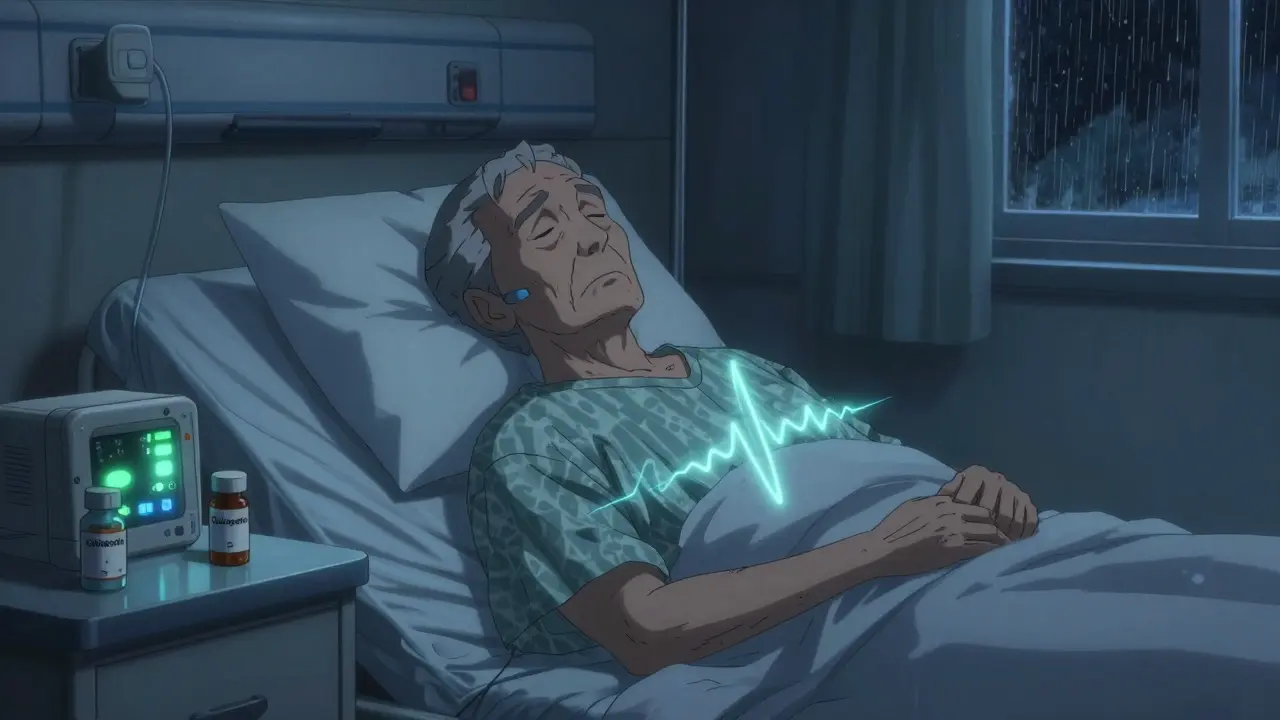

Not everyone who takes this combo will have a problem. But some people are walking into a minefield without knowing it.- Older adults (65+): Their kidneys clear drugs slower. Gabapentinoids build up. Sedation hits harder.

- People with sleep apnea or COPD: Their breathing is already compromised. Add opioids and gabapentinoids? Their lungs can’t compensate.

- Those with kidney problems: Gabapentin and pregabalin are cleared by the kidneys. Even mild impairment increases risk.

- Patients on high opioid doses: The higher the opioid, the more the gabapentinoid amplifies the danger.

- People taking other sedatives: Benzodiazepines, alcohol, sleep meds - they stack on top of this combo like layers of risk.

The Evidence: Rare or Real?

Some studies say the risk is low. A 2020 JAMA study of over 16,000 patients found the absolute risk of serious events was small - you’d need to treat more than 16,000 people before one serious harm occurred. That sounds reassuring. But numbers like that hide the truth. Because when harm happens, it’s often fatal. A UK study of death records found gabapentinoid-opioid co-prescription increased accidental overdose risk by 38%. Another analysis showed a 2.3-fold increase in death risk. The FDA didn’t issue a boxed warning - the strongest safety alert they have - based on theoretical concerns. They did it because real people died. The problem isn’t just that trials don’t always show clear results. It’s that we can’t ethically test this combo in high-risk groups. So we rely on real-world data: hospital records, death certificates, patient reports. And those tell a consistent story: this combination kills.What Regulators Are Doing

In December 2019, the FDA required all gabapentinoid labels to include a boxed warning about respiratory depression, especially when combined with opioids. The European Medicines Agency followed. The UK’s MHRA issued a safety update in 2022 confirming gabapentin alone can cause severe respiratory depression - but the risk skyrockets with opioids. Guidelines changed fast. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria now says: avoid this combo. NICE in the UK updated its low back pain guidelines in 2023 to recommend against routine use of gabapentinoids with opioids. The American Society of Anesthesiologists now says: if you must use them together, monitor closely. Prescriptions are falling. U.S. gabapentinoid sales dropped 12% in co-prescribing with opioids between 2018 and 2021. That’s not because doctors stopped using them entirely. It’s because they’re starting to ask: is the benefit worth the risk?

When Is It Still Okay?

Some patients still need this combination. Chronic pain patients, especially those with nerve damage, may find relief that nothing else provides. But the rules have changed.- Use the lowest dose possible. For pregabalin, that’s 75 mg/day, not 150 mg. For gabapentin, 300 mg/day, not 900 mg.

- Never start high. Begin with half the usual dose and go slow.

- Screen for risk factors. Ask about sleep apnea, COPD, kidney disease, and past sedative use.

- Monitor closely. In hospitals, use pulse oximetry and capnography for the first 24-72 hours. At home, family members should check for slow breathing, confusion, or unresponsiveness.

- Document the decision. Informed consent now includes respiratory depression risk. If it’s not on the form, ask why.

What You Should Do

If you’re taking gabapentin or pregabalin with an opioid:- Ask your doctor: Is this combo necessary? Is there a safer alternative?

- Know the signs of respiratory depression: slow or shallow breathing, blue lips or fingernails, extreme drowsiness, confusion, inability to wake up.

- Have naloxone on hand if you’re at high risk. It won’t reverse gabapentinoid effects - but it can reverse the opioid part, buying time.

- Don’t drink alcohol. Don’t take sleep aids. Don’t combine with benzodiazepines.

- If you’re scheduled for surgery, tell your anesthesiologist you’re on gabapentinoids. They may hold it for a few days before and after.

The Future: Safer Pain Management

Researchers are working on solutions. A 2023 study found genetic differences in the α2δ-1 protein - the target of gabapentinoids - might explain why some people are far more sensitive to respiratory depression. That could lead to genetic tests to identify high-risk patients before prescribing. The CDC’s 2022 opioid guidelines say: avoid this combo when possible. And if you must use it, use the lowest dose and monitor closely. A risk calculator is being developed by the American Pain Society, expected in mid-2024. It will use 12 factors - age, kidney function, opioid dose, BMI, sleep apnea history - to predict risk with 87% accuracy. That’s not perfect, but it’s a start. The goal isn’t to ban gabapentinoids. It’s to use them smarter. Pain matters. But breathing matters more.Can gabapentin or pregabalin cause respiratory depression on their own?

Yes. While the risk is higher when combined with opioids, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency confirmed in 2022 that gabapentin alone has been linked to rare but severe cases of respiratory depression. This is especially true in older adults, people with kidney disease, or those taking high doses. It’s not common, but it’s real - and it’s why boxed warnings were added to all gabapentinoid labels.

How long does the risk last after surgery?

The highest risk is in the first 24 to 72 hours after surgery, when both medications are at peak levels and the body is recovering. Patients are often drowsy, lying flat, and may not be monitored closely. This is why hospitals now recommend continuous oxygen and carbon dioxide monitoring for high-risk patients during this window. The risk doesn’t vanish after 72 hours, but it drops significantly as the body adjusts and opioid doses are tapered.

Is there a safe dose of gabapentinoids when taken with opioids?

There’s no guaranteed safe dose, but lower doses reduce risk. For pregabalin, start at 75 mg per day or less. For gabapentin, 300 mg per day or less is preferred. Doses above 900 mg/day of gabapentin or 150 mg/day of pregabalin significantly increase danger. Always start low, go slow, and monitor for drowsiness or breathing changes. Even low doses can be dangerous in high-risk patients like those with sleep apnea or kidney issues.

Can naloxone reverse respiratory depression from this combo?

Naloxone can reverse the opioid part of the respiratory depression, but it does nothing for the gabapentinoid effect. In many cases, it can help - especially if the patient has a high opioid dose - but it’s not a full solution. If someone is unresponsive and breathing slowly after taking both drugs, call emergency services immediately. Naloxone may buy time, but they still need medical care.

Why do some doctors still prescribe this combo?

Some doctors still prescribe it because they’ve seen it work - patients report better pain control and lower opioid use. But the evidence is mixed. Many haven’t been trained on the latest safety warnings, or they assume the risk is too low to worry about. Others are unaware that guidelines now strongly discourage this practice. The shift is happening, but it’s slow. Patients should ask: "Is this really necessary? Are there alternatives?"

What are the alternatives to gabapentinoids for nerve pain?

For nerve pain, alternatives include duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor), topical lidocaine, capsaicin patches, or physical therapy. In some cases, non-opioid pain relievers like acetaminophen or NSAIDs (if safe) can be combined with non-pharmacological options like cognitive behavioral therapy or acupuncture. The key is to avoid adding another CNS depressant. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor - especially if you’re already on opioids.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us