When a doctor prescribes a generic drug, they expect it to work just like the brand-name version. It’s the same active ingredient, same dosage, same instructions. But what if the pill you’re taking was made in a factory halfway across the world-with no warning, no transparency, and no way to know if it was made under the same standards?

Why clinicians are starting to ask hard questions

Clinicians aren’t against generics. In fact, they’ve long supported them as a way to cut costs and keep care affordable. But something has changed. Over the past decade, the manufacturing of generic drugs has shifted dramatically. Today, only 14% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are made in the U.S. More than half come from just two countries: India and China. And for older, low-cost generics-drugs that have been on the market for years and face intense price pressure-the quality has started to slip.A 2023 study from Ohio State University looked at over 1.5 million adverse event reports in the FDA’s database. What they found was startling: generic drugs made in India were linked to a 54% higher rate of severe adverse events-including hospitalizations, disabilities, and deaths-compared to identical generics made in the U.S. This wasn’t a random spike. It was consistent across multiple drugs, especially those that had been on the market for 10 years or more. As one researcher put it, "When drugs get cheaper and cheaper, and competition gets more intense to hold down costs, operations and supply chains start to break down."

The hidden complexity of a single pill

Most people think of a generic drug as one product made in one place. It’s not. A single pill can pass through five or six different facilities before it reaches your pharmacy. The active ingredient might be made in a chemical plant in Hyderabad. The inactive ingredients-fillers, binders, coatings-could come from a lab in New Jersey. The tablet might be pressed in a factory in Mexico, then packaged in a warehouse in Florida. Only one company appears on the label, but the real production chain is a global puzzle with no clear map.And here’s the kicker: the FDA requires generics to prove they’re "bioequivalent"-meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient at the same rate as the brand-name drug. That sounds solid. But bioequivalence doesn’t guarantee consistency over time. It doesn’t catch impurities. It doesn’t check for batch-to-batch variation. And it doesn’t account for what happens when a factory cuts corners to save a few cents per pill.

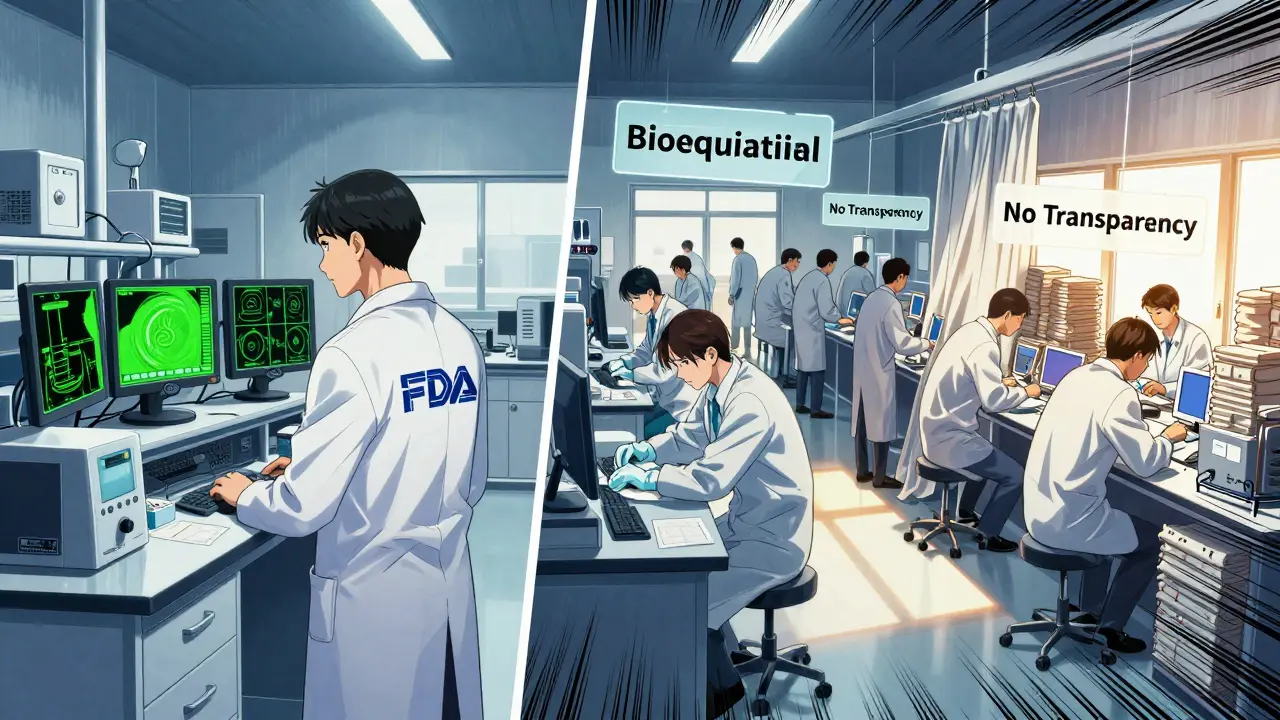

Inspections that don’t inspect

The FDA inspects U.S. manufacturing sites without warning. That’s a big deal. It means factories can’t clean up before the inspectors show up. They can’t hide problems. They have to run clean every day.But for overseas facilities? Inspections are scheduled weeks or months in advance. That gives manufacturers time to prep-rearrange equipment, hire extra staff, flush out defective batches. One researcher compared it to inviting someone to your house only after you’ve scrubbed every surface and hidden the mess. "It makes it harder for the FDA to find those that do exist," said Professor Robert S. Gray, lead author of the Ohio State study.

The result? U.S.-based generics have fewer recalls, fewer shortages, and fewer reports of patient harm. Overseas-made generics? The numbers tell a different story. In 2022, nearly 60% of all drug shortages in the U.S. were linked to manufacturing quality issues-and most of those came from overseas suppliers. These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re systemic.

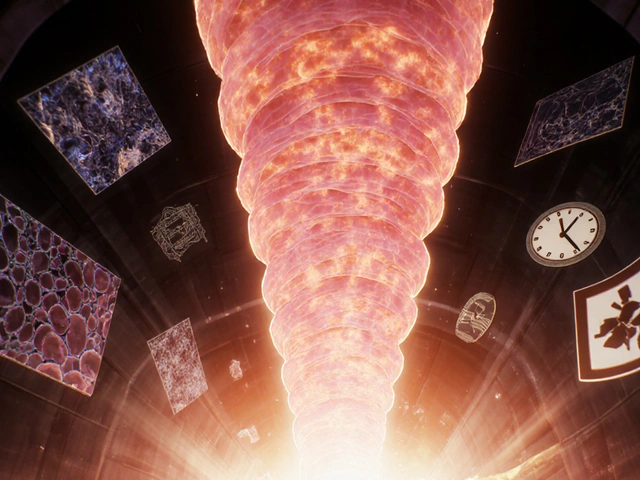

Advanced manufacturing could change everything

There’s a better way. Advanced manufacturing technologies (AMTs)-like continuous manufacturing and real-time process monitoring-are already being used in the U.S. to make drugs faster, cheaper, and with far fewer errors. Over 80% of drugs made using these technologies are produced domestically. These systems track every step of production. If a batch starts to deviate, the machine stops it before it becomes a problem.But here’s the catch: AMTs require big upfront investment. A single continuous manufacturing line can cost $50 million or more. For a company making pennies per pill, that’s not a smart business move. So while the technology exists, it’s not being used where it’s needed most-on the low-cost generics that are driving the quality crisis.

Domestic production isn’t just patriotic-it’s practical

The University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy put it plainly: "If we have more generic manufacturing happening domestically, we would ideally have fewer quality concerns, fewer shortages, and a more stable supply chain."It’s not about nationalism. It’s about control. When a drug is made in the U.S., the FDA can inspect it without notice. When a problem arises, the recall is faster. When a factory shuts down, you don’t have to wait for a shipment from another continent. And when a patient has a reaction, you can trace it back-fast.

Some argue that global supply chains bring efficiency and lower prices. But when a shortage delays cancer treatment or forces a hospital to ration insulin, the cost isn’t just financial-it’s human. And when a generic drug causes a preventable death, the savings evaporate.

What’s being done-and what’s not

The FDA says the system is working. "The U.S. drug supply chain remains one of the safest in the world," they claim. But their own data contradicts that. The Ohio State study didn’t find a flaw in the FDA’s approval process-it found a flaw in how they monitor manufacturing after approval.Some experts are pushing for transparency. They want the country of manufacture listed on every generic drug label. Imagine walking into a pharmacy and seeing: "Made in India" or "Made in U.S." That simple change could shift market demand. If patients and doctors start choosing U.S.-made generics-even if they cost a little more-the industry will have to respond.

Others want the FDA to stop scheduling inspections overseas. Unannounced visits should be the rule, not the exception. But so far, the FDA hasn’t changed its policy.

Meanwhile, some hospitals and health systems are taking matters into their own hands. A few have started requiring proof of quality certification from suppliers. Others are switching to U.S.-made generics for critical medications like heparin, epinephrine, and insulin. These aren’t radical moves. They’re practical ones.

It’s not just about generics

Let’s be clear: brand-name drugs aren’t immune to quality problems. Substandard and counterfeit drugs exist across the board. But generics are under more pressure to cut costs, which makes them more vulnerable. And because they’re used so widely-by millions of patients, including those with chronic conditions, low income, or no insurance-the stakes are higher.One pharmacist summed it up in a 2023 NIH article: "Is the quality of generic drugs cause for concern? Yes."

That’s not fearmongering. That’s experience.

What clinicians can do

You don’t need to stop prescribing generics. But you can start asking questions:- Where is this drug made?

- Has there been a recent recall or warning from the FDA?

- Is there a U.S.-made alternative available?

- For high-risk patients-elderly, immunocompromised, or on narrow-therapeutic-index drugs-should we consider brand-name or domestically made generics?

There’s no need to panic. Most generics are still safe. But complacency is dangerous. The system that worked 20 years ago doesn’t work the same way today. The supply chain is longer. The oversight is weaker. The incentives are misaligned.

It’s time to treat drug quality like patient safety-because it is.

Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

No, generic drugs are required by the FDA to have the same active ingredient, strength, and dosage form as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence-meaning they work the same way in the body. But bioequivalence doesn’t guarantee consistent quality over time, especially for older generics made overseas. Problems arise not from the drug’s design, but from manufacturing practices-like poor raw materials, inconsistent mixing, or inadequate quality control.

Why are so many generic drugs made in India and China?

The main reason is cost. Labor, regulatory compliance, and facility maintenance are significantly cheaper in these countries. After the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act made it easier to approve generics, manufacturers shifted production overseas to maximize profits. Over time, a few large companies in India and China came to dominate the market, creating a supply chain that’s efficient but fragile. When geopolitical tensions, trade restrictions, or quality failures occur, the entire system feels the impact.

Can the FDA be trusted to ensure generic drug safety?

The FDA has a strong track record with U.S.-based manufacturers. But their ability to oversee overseas facilities is limited. They inspect foreign sites less frequently, and inspections are scheduled in advance-giving manufacturers time to hide problems. A 2023 study found that the inspection process for overseas plants is less effective at catching quality issues. While the FDA has the authority to act, it hasn’t yet changed its inspection protocols globally, despite clear evidence that this gap contributes to adverse events.

Should I avoid generic drugs altogether?

No. Most generics are safe and effective. But for critical medications-like blood thinners, seizure drugs, or heart medications-it’s worth asking your pharmacist or provider if a U.S.-made version is available. If you notice a change in how a generic drug works for you-side effects, lack of effectiveness, or new symptoms-it’s not "all in your head." It could be a batch issue. Report it to your doctor and to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

Is there a way to know where my generic drug was made?

Right now, the country of manufacture isn’t listed on the label. You can sometimes find this information by asking your pharmacist or checking the manufacturer’s website-but it’s not easy. Some hospitals and pharmacy chains are starting to track this data internally. Advocates are pushing for federal rules requiring country-of-origin labeling on all generic drugs. Until then, transparency remains a gap in the system.

What’s being done to fix this problem?

Some researchers and health systems are calling for three key changes: (1) Unannounced FDA inspections for all manufacturing sites, regardless of location; (2) Mandatory labeling of the country of manufacture for generics; and (3) Financial incentives for companies to use advanced manufacturing technologies in the U.S. A few states have begun pilot programs to prioritize U.S.-made generics for public health programs. But federal action has been slow. The tension remains: lower cost versus higher safety.