When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, the label might look like any other. But if it’s a controlled substance, there’s more going on beneath the surface. The controlled substance labels you see aren’t just about dosage and directions-they’re tied to a federal system that determines how the drug is made, prescribed, tracked, and even sold. This system, created by the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970, divides drugs into five categories called schedules. Each schedule has its own rules, and getting them wrong can mean legal trouble for doctors, pharmacists, and patients alike.

What Are the Five Drug Schedules?

The DEA classifies controlled substances into five schedules based on three things: how likely they are to be abused, whether they have any medical use, and how dangerous they are if misused. These aren’t arbitrary groupings-they’re backed by scientific reviews from the FDA and the Department of Health and Human Services.Schedule I drugs have no accepted medical use in the U.S. and a high potential for abuse. This includes heroin, LSD, and marijuana-at least under federal law. Even though 38 states allow medical marijuana, it’s still federally illegal. That’s why you won’t find a Schedule I prescription on your counter.

Schedule II drugs have high abuse potential but are used medically. These are the strong opioids: oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine, and Adderall. Prescriptions for these can’t be refilled. You need a new written prescription each time, and in most states, it must be on special tamper-resistant paper. Electronic prescriptions are allowed in some cases, but they’re tightly controlled.

Schedule III substances have less abuse potential than Schedule II. Think hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Vicodin), ketamine, and some anabolic steroids. These can be refilled up to five times in six months. Pharmacists see these more often than Schedule II drugs-they make up nearly half of all controlled substance prescriptions.

Schedule IV includes drugs like Xanax, Valium, and Ambien. These are used for anxiety and sleep disorders. Abuse potential is low, but dependence can still happen. Refills are allowed up to five times in six months, and electronic prescriptions are standard.

Schedule V is the least restricted. These are cough syrups with tiny amounts of codeine, antidiarrheal meds with diphenoxylate, and pregabalin. Some can even be bought over-the-counter in limited quantities, with the pharmacist keeping a log. You won’t need a full prescription for these in most cases.

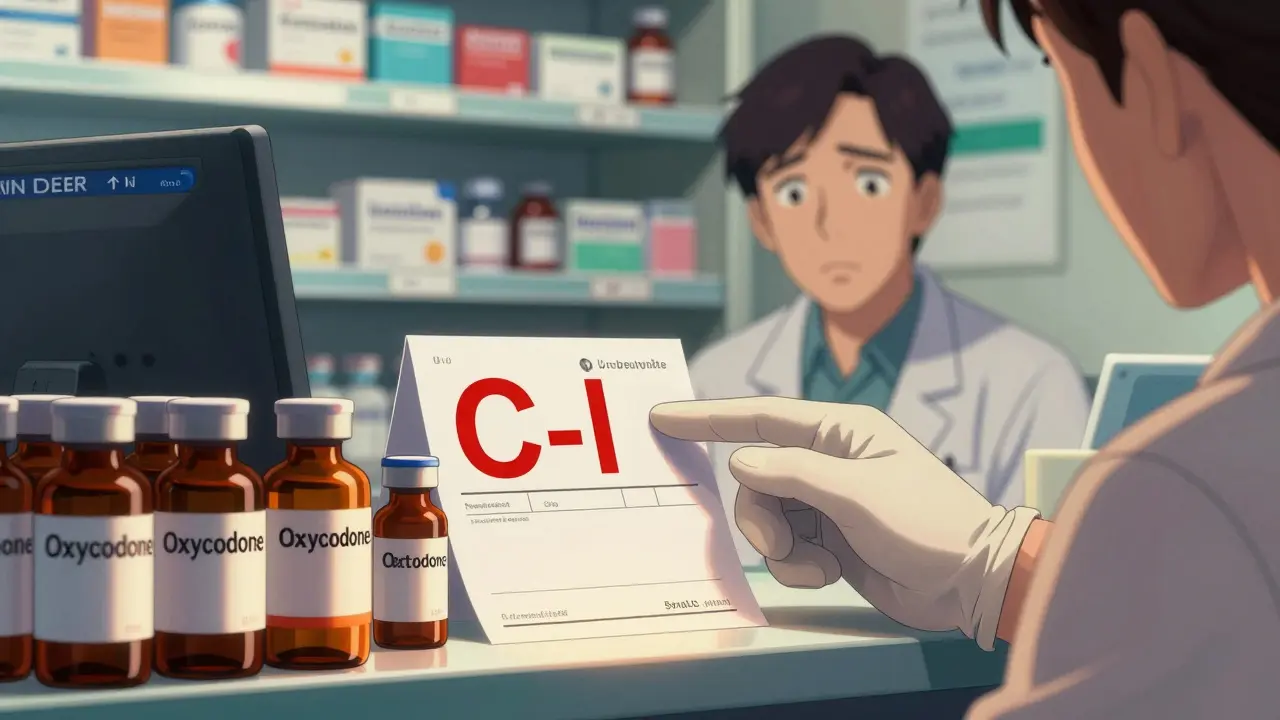

Why Do Labels Look Different?

If you’ve ever noticed a tiny “C-II” or “C-III” on a prescription label, that’s the DEA schedule code. It’s not just for show. It tells the pharmacy exactly what rules to follow. A Schedule II label might say “No Refills” in bold. A Schedule IV label might say “Refills: 5.” The label also includes the DEA registration number of the prescriber, which must be printed clearly.Pharmacies use these codes to trigger internal checks. If a Schedule II prescription comes in without a DEA number, it’s rejected. If a patient tries to refill a Schedule II drug too early, the system flags it. That’s why you might get a call from the pharmacy asking for a new prescription-even if your doctor said you could refill it.

Some drugs appear in multiple schedules depending on their formulation. Codeine is a good example. Pure codeine is Schedule II. Codeine combined with acetaminophen (in 15mg or higher doses) is Schedule III. If the dose is under 200mg per 100ml, like in some cough syrups, it’s Schedule V. That’s why the exact dosage on the label matters as much as the drug name.

How Do Prescribers Handle These Drugs?

Doctors don’t just write prescriptions for controlled substances like they do for antibiotics. They need their own DEA registration number-a unique code that looks like “AB1234567.” Getting one takes 4 to 6 weeks. New doctors spend an average of 12.5 hours learning how to handle these prescriptions during residency.For Schedule II drugs, the rules are strict. In 47 states, the prescription must be a physical paper copy. Electronic prescriptions are allowed, but only under specific conditions. Each one must be signed digitally with a secure key. Pharmacies must store these records separately from regular prescriptions.

One oncology nurse reported that processing a single Schedule II prescription takes 15 minutes longer than a regular one. Why? Because every step has to be documented: who ordered it, who dispensed it, when, and why. A 2022 DEA audit found that 43% of compliance violations involved missing or incomplete records for Schedule II drugs.

Meanwhile, Schedule III to V prescriptions are easier. Electronic prescriptions are standard. Partial fills are allowed. A patient can pick up part of the prescription now and the rest later. This flexibility helps with chronic pain management, but it also means pharmacists have to track multiple pick-ups for the same prescription.

What’s Wrong With the System?

The schedule system was designed in 1970. Back then, we didn’t know as much about addiction, mental health, or drug metabolism. Today, experts say it’s outdated.Take cannabis. It’s still Schedule I-no medical use, high abuse potential. But over 2 million Americans use it legally for pain, epilepsy, or nausea from chemotherapy. Thirty-eight states have legalized it. The federal government has acknowledged the contradiction. In August 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services recommended moving cannabis to Schedule III. If that happens, it would be the biggest change to the system in over 50 years.

Another problem? The system doesn’t always match real-world risk. Fentanyl is Schedule II and kills thousands every year. Xanax is Schedule IV and is often misused, but it’s not treated with the same level of scrutiny. A 2023 survey of pharmacists found that 78% believe the current system creates unnecessary barriers for patients who need these drugs.

Some addiction specialists argue the system still works. “The clear difference between schedules helps patients understand risk,” said one clinic director in a 2022 interview. But others, like psychotherapist Benjamin Zelinsky, say, “It can give people an understanding of the risks for certain substances, but, as we’ve seen, it’s not really an effective tool.”

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond?

The DEA is under pressure to modernize. In October 2025, the agency updated its Controlled Substance Code Number list for the first time in two years. That’s faster than the old average of 24 months per decision. The goal is to get new synthetic drugs-like fentanyl analogs or designer stimulants-into the right schedule within 12 months.Industry experts predict more changes. A 2023 Deloitte survey found that 68% believe at least two Schedule I substances (likely cannabis and MDMA) will be rescheduled by 2028. The Rand Corporation predicts the system could expand to six or seven schedules within 15 years to better reflect risk levels.

Meanwhile, compliance costs are rising. Pharmaceutical companies spend about $2.3 billion a year just to follow the rules. Pharmacies invest in special software to track controlled substances. Doctors pay for training and secure e-prescribing systems. All of this is meant to prevent diversion, but it also slows down care.

What Should Patients Know?

If you’re taking a controlled substance, here’s what you need to remember:- Check your label for the “C-II,” “C-III,” etc. That tells you how many refills you’re allowed.

- Schedule II drugs? No refills. You’ll need a new prescription every time.

- If your doctor changes the dose or formulation, the schedule might change-even if the drug name stays the same.

- Never share your medication. Even if it’s a Schedule IV drug like Xanax, giving it to someone else is illegal.

- If your pharmacy refuses to refill a prescription, it’s not being difficult-they’re following federal law.

It’s not about distrust. It’s about safety. The system exists to keep dangerous drugs out of the wrong hands. But it’s also a reminder that not all medications are created equal. The label you see? It’s not just instructions. It’s a legal document.

What does a C-II label mean on a prescription?

A C-II label means the drug is classified under Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act. These are high-risk medications with accepted medical uses, like oxycodone or fentanyl. Prescriptions for C-II drugs cannot be refilled and must be written on tamper-resistant paper in most states. Electronic prescriptions are allowed but require strict digital authentication.

Can a Schedule III drug be refilled?

Yes, Schedule III drugs can be refilled up to five times within six months from the original prescription date. Examples include hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) and ketamine. Electronic prescriptions are permitted, and partial fills are allowed, meaning you can pick up part of the prescription now and the rest later.

Why is marijuana still Schedule I if it’s legal in my state?

Marijuana remains federally classified as Schedule I under the Controlled Substances Act, meaning the U.S. government considers it to have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Even though 38 states have legalized it for medical use, federal law still overrides state law. The Department of Health and Human Services recommended rescheduling it to Schedule III in August 2023, but the final decision is pending as of early 2026.

Are all opioids Schedule II?

No. Pure opioids like morphine and fentanyl are Schedule II. But when opioids are combined with other drugs in lower doses, they can be Schedule III or even Schedule V. For example, codeine combined with acetaminophen in doses over 15mg per tablet is Schedule III, while cough syrups with less than 200mg of codeine per 100ml are Schedule V.

Do I need a DEA number to prescribe controlled substances?

Yes. Any licensed prescriber who writes prescriptions for controlled substances must have a DEA registration number. This number is required on every prescription and is used to track who is prescribing what. The DEA issues these numbers after background checks, and processing takes 4 to 6 weeks. Without this number, prescriptions for Schedule II-V drugs will be rejected by pharmacies.

Can pharmacists refuse to fill a controlled substance prescription?

Yes. Pharmacists are legally allowed-and sometimes required-to refuse to fill a controlled substance prescription if they suspect fraud, abuse, or if the prescription doesn’t meet legal requirements. This includes missing DEA numbers, incorrect dosage, or attempts to refill Schedule II drugs. Refusing to fill a prescription is not discrimination; it’s part of their legal duty under the Controlled Substances Act.

If you’re prescribed a controlled substance, ask your pharmacist to explain the schedule code on your label. Understanding it can help you avoid surprises and stay compliant with the law. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s designed to protect you-and others-from harm.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us