Diabetes Medication Pancreatitis Risk Calculator

Pancreatitis Risk Comparison

Understand the relative risk of pancreatitis for different diabetes medications based on clinical studies. This tool helps compare the safety profiles of common diabetes treatments.

Medication Risk Comparison

| Medication Class | Relative Risk | Absolute Risk | Key Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 Inhibitors (Gliptins) | ROR 13.2 | 0.14% higher incidence |

Strongest signal in pharmacovigilance data (1 extra case per 834 patients over 2.4 years) |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | ROR 9.65 | Moderate risk |

Liraglutide has clearest link; others less clear (1 extra case per 500-600 patients over 2 years) |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Low | Very low risk |

Significantly lower risk than DPP-4 inhibitors (Similar to baseline risk) |

| Metformin | Neutral | Neutral risk | No increased risk found in large studies |

| Sulfonylureas | Neutral | Neutral risk | Low risk but higher hypoglycemia risk |

Key Insights from Research

These risk ratios are based on large studies and clinical trials. While absolute risk is low, it's important to know:

- Approximately 17.7% of reported pancreatitis cases associated with DPP-4 inhibitors were classified as severe

- The risk is class-wide - all DPP-4 inhibitors carry similar risk (linagliptin is not safer)

- For many patients, the benefits of DPP-4 inhibitors outweigh the risks, but alternative medications offer better safety profiles

- Stopping the medication usually leads to improvement in pancreatitis cases

What Should You Do?

Immediate Action for Pancreatitis Symptoms

Severe, constant abdominal pain radiating to the back, nausea, vomiting, and fever are warning signs.

- Get blood tests for amylase and lipase

- Consider abdominal imaging (ultrasound/CT)

- Report the event to your country's drug safety agency

Prevention for High-Risk Patients

Patients with any of these factors should discuss alternatives with their doctor:

- History of pancreatitis

- Chronic gallstones or bile duct disease

- Heavy alcohol use

- Very high triglyceride levels (above 500 mg/dL)

- Obesity with metabolic syndrome

When you’re managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing other problems is the goal. DPP-4 inhibitors-also called gliptins-were once seen as a safe, easy option. They don’t make you gain weight. They rarely cause low blood sugar. And unlike some older drugs, they don’t raise your risk of heart attacks. But behind those benefits is a quiet, serious risk: pancreatitis.

What Are DPP-4 Inhibitors?

DPP-4 inhibitors are oral diabetes pills that work by blocking an enzyme called dipeptidyl peptidase-4. This lets your body keep more of its natural incretin hormones, which help the pancreas release insulin after meals and slow down glucagon, the hormone that tells your liver to dump sugar into your blood. The result? Better blood sugar control without the crashes or weight gain you get with some other drugs.

The first one, sitagliptin (Januvia), hit the market in 2006. Since then, others followed: saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), alogliptin (Nesina), and vildagliptin (not available in the U.S.). Together, they make up about 15% of all oral diabetes prescriptions in the U.S., according to 2022 data. For many people, they’re a good fit-especially if they’re already on metformin and need a second drug that’s gentle on the body.

Pancreatitis: A Rare but Real Danger

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. It can start with mild discomfort but quickly turn life-threatening. Symptoms include severe, constant pain in the upper abdomen that radiates to your back, nausea, vomiting, and fever. If you’ve had gallstones, heavy alcohol use, or high triglycerides, your risk is already higher. Now, add a DPP-4 inhibitor, and that risk goes up.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t common. But it’s not a myth either. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology looked at over 100,000 patients and found a reporting odds ratio of 13.2 for pancreatitis with DPP-4 inhibitors. That means people taking these drugs were over 13 times more likely to have a case reported than those not taking them. Other studies confirm this. One meta-analysis of nearly 54,000 patients found a 54% higher risk. Another showed one extra case of pancreatitis for every 834 people treated for 2.4 years.

The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) confirmed this risk back in 2012. The FDA followed with labeling updates. And yet, many patients-and even some doctors-still don’t know about it. Why? Because the absolute risk is low. For most people, the chance of developing pancreatitis is still under 0.2%. But when it happens, it’s serious. About 17.7% of reported cases were classified as severe, requiring hospitalization or leading to complications.

How Do We Know It’s the Drug and Not the Diabetes?

It’s a fair question. People with type 2 diabetes already have a higher baseline risk of pancreatitis than those without diabetes. So how do we know the drug is the culprit?

Large clinical trials compared DPP-4 inhibitors directly to placebo or other diabetes drugs. Even when researchers controlled for age, weight, alcohol use, and gallstones, the DPP-4 group still had more pancreatitis cases. In the CVOT trials for saxagliptin, alogliptin, and sitagliptin-studies designed to test heart safety-there was a consistent, though small, imbalance in pancreatitis numbers. The pattern didn’t change even when the trials were pooled together.

Real-world data from 1.2 million patients in a 2023 study confirmed the same thing: a 0.14% higher incidence of pancreatitis in those on DPP-4 inhibitors. And when patients stopped taking the drug, the pancreatitis usually got better. That’s a key clue-if the problem clears up after you stop the medication, it’s likely the drug caused it.

How Do DPP-4 Inhibitors Compare to Other Diabetes Drugs?

Not all diabetes medications carry the same risk. Here’s how DPP-4 inhibitors stack up:

| Drug Class | Relative Risk of Pancreatitis | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 Inhibitors (Gliptins) | High (ROR 13.2) | Strongest signal in pharmacovigilance data |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Medium (ROR 9.65) | Liraglutide has the clearest link; others less clear |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Low | Significantly lower risk than DPP-4 inhibitors |

| Metformin | Neutral | No increased risk found in large studies |

| Sulfonylureas | Neutral | Low risk, but higher hypoglycemia risk |

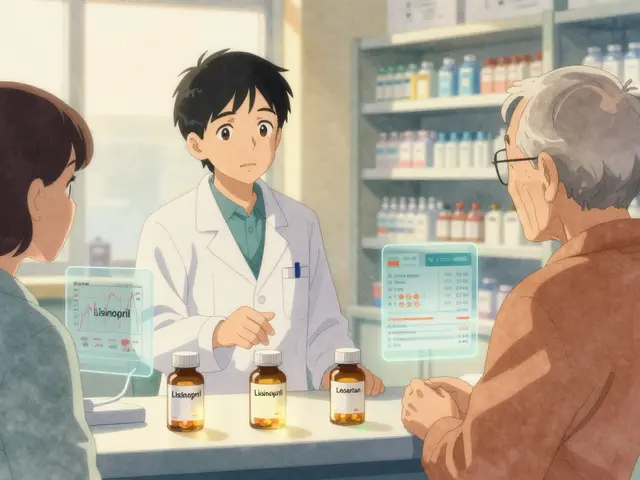

GLP-1 agonists like liraglutide and semaglutide also carry a pancreatitis risk-but it’s lower than with DPP-4 inhibitors. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin), on the other hand, are now preferred by many doctors because they don’t raise pancreatitis risk and even protect the heart and kidneys. They’re becoming the go-to second-line option for many patients.

What Should You Do If You’re Taking a DPP-4 Inhibitor?

If you’re on one of these drugs and feel fine, don’t panic. The risk is low. But you should be aware. Here’s what to do:

- Know the symptoms. Sudden, severe belly pain that doesn’t go away, especially if it spreads to your back, is the biggest red flag. Nausea, vomiting, and fever often follow.

- Don’t ignore mild symptoms. Even if you think it’s just indigestion, if it lasts more than a day or two, get it checked. A simple blood test for amylase and lipase (pancreatic enzymes) can catch early signs.

- Ask for an ultrasound. If your doctor suspects pancreatitis, they should check for gallstones, which can trigger it. DPP-4 inhibitors don’t cause gallstones, but if you already have them, the drug might make things worse.

- Stop the drug if pancreatitis is suspected. In most cases, stopping the medication leads to improvement. The MHRA says that’s the most important step.

- Report it. If you or your doctor think a DPP-4 inhibitor caused pancreatitis, report it to your country’s drug safety system-like the FDA’s MedWatch or the UK’s Yellow Card scheme. This helps regulators track the risk better.

Who Should Avoid DPP-4 Inhibitors?

You don’t need to avoid them if you’re otherwise healthy. But if you have any of these, talk to your doctor before starting one:

- A history of pancreatitis (even if it was years ago)

- Chronic gallstones or bile duct disease

- Heavy alcohol use

- Very high triglyceride levels (above 500 mg/dL)

- Obesity with metabolic syndrome

For these patients, SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists are often better choices. They offer similar blood sugar control without the pancreatitis risk-and in some cases, they actually protect your heart and kidneys.

Are DPP-4 Inhibitors Still Used Today?

Yes. They’re still on the American Diabetes Association’s recommended list for type 2 diabetes treatment. Why? Because for most people, the benefits outweigh the risks. They’re convenient (once-daily pills), don’t cause weight gain, and have a low chance of low blood sugar. And unlike some older drugs, they don’t raise heart attack risk.

But the landscape is changing. Newer drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists are now preferred as second-line treatments because they offer more than just blood sugar control-they reduce heart failure, kidney damage, and even death in high-risk patients. DPP-4 inhibitors are no longer the first choice for most people with heart or kidney problems.

Global sales for DPP-4 inhibitors hit $5.8 billion in 2022, but growth is slowing. Meanwhile, GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic and Mounjaro are booming. That’s not just because they’re trendy-it’s because they’re more effective and safer for long-term health.

What’s Next?

Researchers are now looking for genetic markers that might predict who’s most likely to develop pancreatitis on DPP-4 inhibitors. If we can find those markers, we could test patients before prescribing these drugs-and avoid the problem entirely.

For now, the message is simple: DPP-4 inhibitors are not dangerous for most people. But they’re not risk-free. If you’re on one, know the signs. If you have risk factors for pancreatitis, ask if there’s a better option. And if you ever feel that deep, unrelenting abdominal pain-don’t wait. Get help.

Can DPP-4 inhibitors cause pancreatic cancer?

No. Multiple large studies, including meta-analyses of over 55,000 patients, have found no link between DPP-4 inhibitors and pancreatic cancer. While pancreatitis itself can be a risk factor for cancer over decades, the drugs themselves do not cause it. This was a concern early on, but current evidence strongly rules it out.

Is linagliptin safer than other DPP-4 inhibitors?

No. All DPP-4 inhibitors carry the same pancreatitis risk. Linagliptin was once thought to be safer because it’s mostly cleared through the bile, not the kidneys, but studies show it still increases pancreatitis risk. A 2021 case report confirmed acute pancreatitis triggered by linagliptin. The risk is class-wide, not drug-specific.

What should I do if I develop pancreatitis while on a DPP-4 inhibitor?

Stop taking the medication immediately and contact your doctor. Pancreatitis can become life-threatening if not treated. Your doctor will likely run blood tests for amylase and lipase, and may order an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan. Most cases improve after stopping the drug, but severe cases require hospital care. Report the event to your country’s drug safety agency.

Are there any alternatives to DPP-4 inhibitors that are safer for the pancreas?

Yes. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin) have a much lower risk of pancreatitis and offer additional heart and kidney protection. GLP-1 receptor agonists (like semaglutide and liraglutide) also carry less risk than DPP-4 inhibitors and are more effective at lowering blood sugar and promoting weight loss. Both are now preferred in most treatment guidelines.

How common are side effects like headaches or cold symptoms with DPP-4 inhibitors?

Headaches and upper respiratory infections (like colds) are the most common side effects, affecting up to 10% of users. These are mild and usually go away on their own. They’re far more common than pancreatitis, which affects fewer than 1 in 1,000 patients. But because pancreatitis is serious, it’s the one you need to watch for.

If you’ve been on a DPP-4 inhibitor for years without issues, you’re likely fine. But if you’re just starting out-or if you’ve had even one episode of unexplained belly pain-talk to your doctor about whether this drug is still the best choice for you. Your pancreas matters as much as your blood sugar.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us